20 Accumulated Local Effects (ALE)

Accumulated local effects (Apley and Zhu 2020) describe how features influence the prediction of a machine learning model on average. ALE plots are a faster and unbiased alternative to partial dependence plots (PDPs).

I recommend reading the chapter on partial dependence plots first, as they are easier to understand, and both methods share the same goal: Both describe how a feature affects the prediction on average. In the following section, I want to convince you that partial dependence plots have a serious problem when the features are correlated.

Motivation and intuition

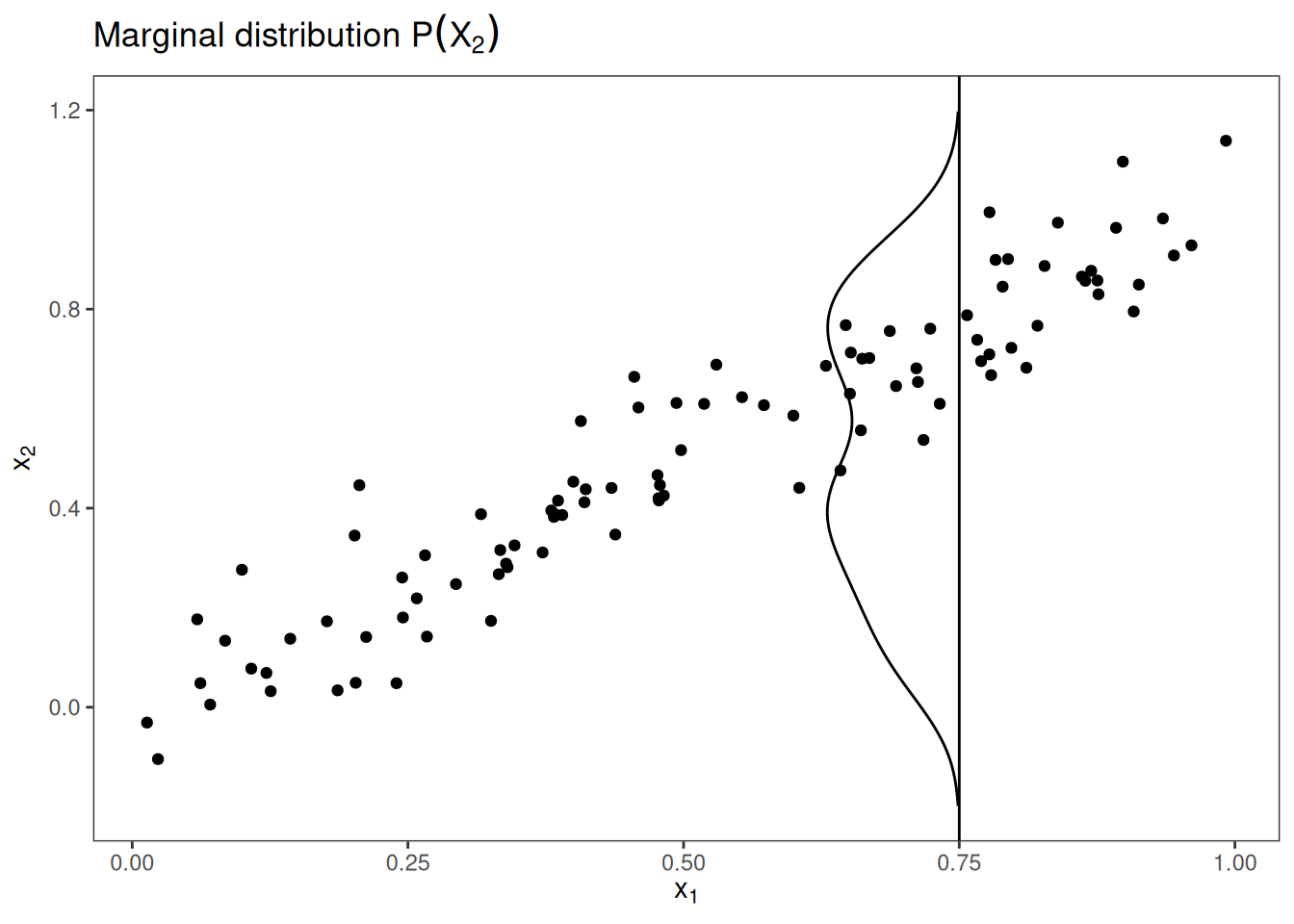

If features of a machine learning model are correlated, the partial dependence plot cannot be trusted. The computation of a partial dependence plot for a feature that is strongly correlated with other features involves averaging predictions of artificial data instances that are unlikely in reality. This can greatly bias the estimated feature effect. Imagine calculating partial dependence plots for a machine learning model that predicts the value of a house depending on the number of rooms and the size of the living area. We’re interested in the effect of the living area on the predicted value. As a reminder, the recipe for partial dependence plots is: 1) Select feature. 2) Define grid. 3) Per grid value: a) Replace feature with grid value and b) average predictions. 4) Draw curve. For the calculation of the first grid value of the PDP – say 30 m2 – we replace the living area for all instances by 30 m2, even for houses with 10 rooms. Sounds to me like a very unusual house. The partial dependence plot includes these unrealistic houses in the feature effect estimation and pretends that everything is fine. Figure 20.1 illustrates two correlated features and how it comes that the partial dependence plot method averages predictions of unlikely instances.

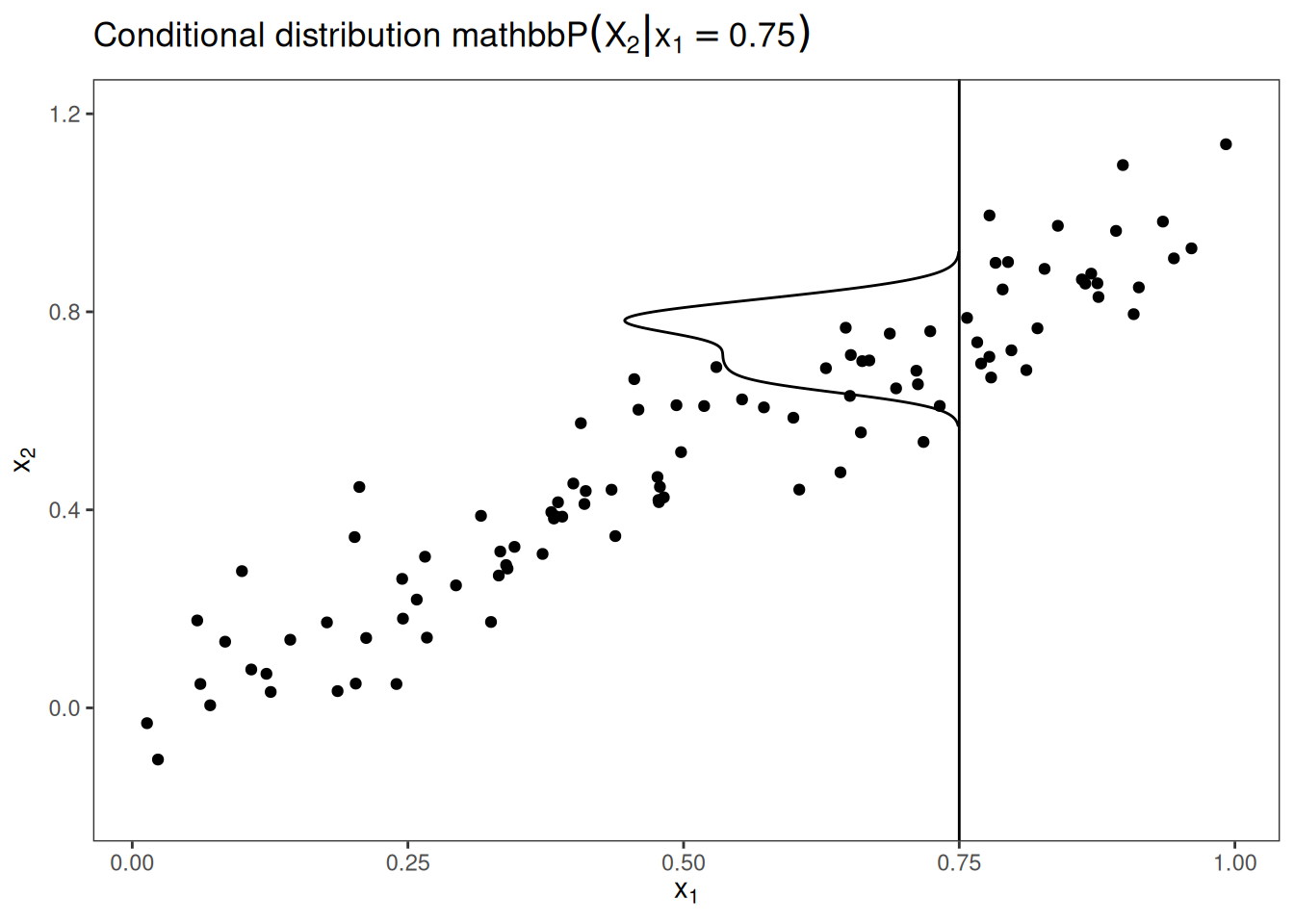

What can we do to get a feature effect estimate that respects the correlation of the features? We could average over the conditional distribution of the feature, meaning at a grid value of \(X_1\), we average the predictions of instances with a similar value for \(X_1\). The solution for calculating feature effects using the conditional distribution is called Marginal Plots, or M-Plots (confusing name, since they are based on the conditional, not the marginal distribution). Wait, did I not promise you to talk about ALE plots? M-Plots are not the solution we are looking for. Why do M-Plots not solve our problem? If we average the predictions of all houses of about 30 m2, we estimate the combined effect of living area and of number of rooms, because of their correlation. Suppose that the living area has no effect on the predicted value of a house, only the number of rooms has. The M-Plot would still show that the size of the living area increases the predicted value, since the number of rooms increases with the living area. Figure 20.2 shows for two correlated features how M-Plots work.

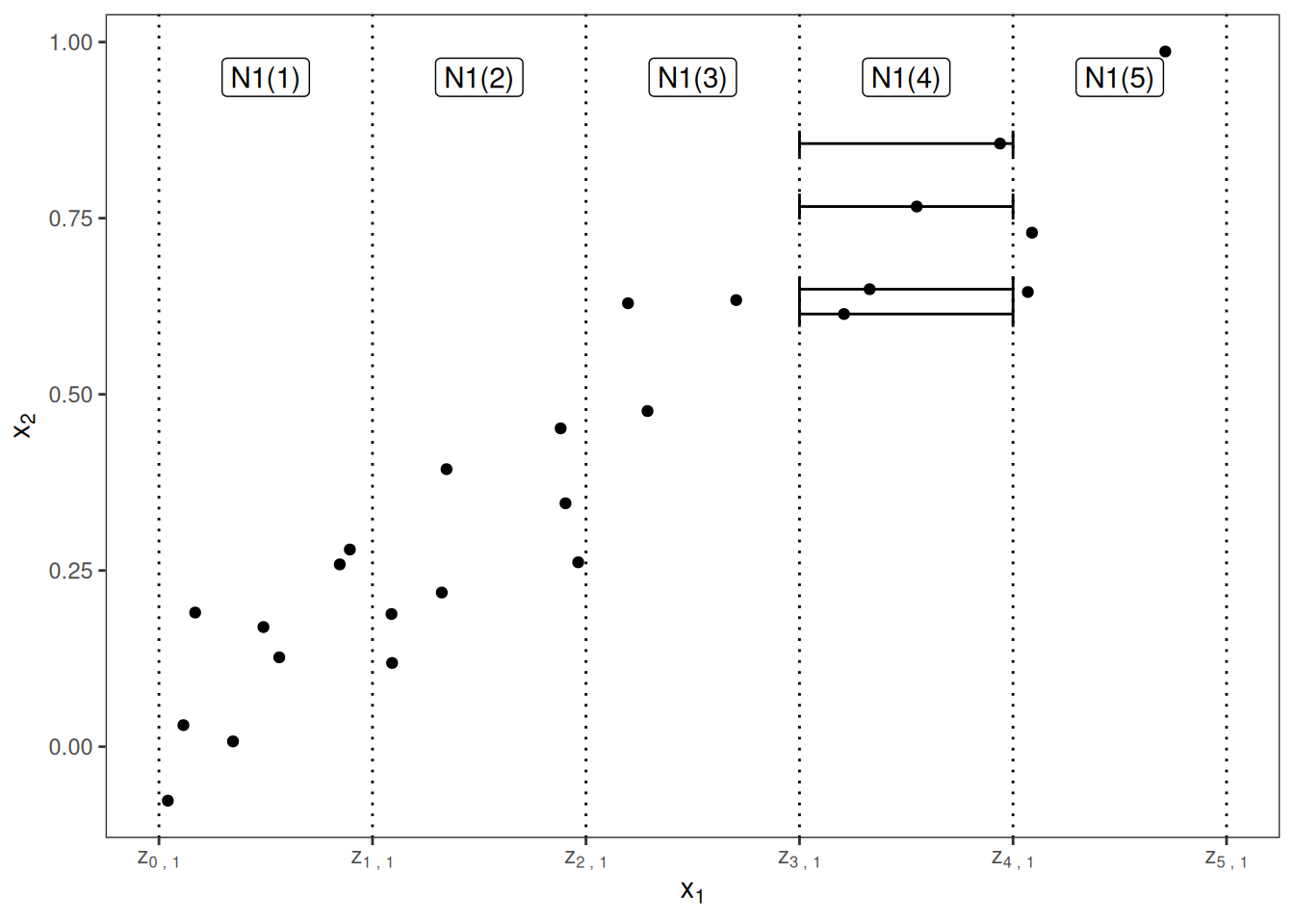

M-Plots avoid averaging predictions of unlikely data instances, but they mix the effect of a feature with the effects of all correlated features. ALE plots solve this problem by calculating – also based on the conditional distribution of the features – differences in predictions instead of averages. For the effect of living area at 30 m2, the ALE method uses all houses with about 30 m2, gets the model predictions pretending these houses were 31 m2, minus the prediction pretending they were 29 m2. This gives us the pure effect of the living area and does not mix the effect with the effects of correlated features. The use of differences blocks the effect of other features. Figure 20.3 provides intuition on how ALE plots are calculated.

To summarize how each type of plot (PDP, M, ALE) calculates the effect of a feature at a certain grid value \(v\):

- Partial Dependence Plots: “Let me show you what the model predicts on average when each data instance has the value \(v\) for that feature. I ignore whether the value \(v\) makes sense for all data instances.”

- M-Plots: “Let me show you what the model predicts on average for data instances that have values close to \(v\) for that feature. The effect could be due to that feature, but also due to correlated features.”

- ALE plots: “Let me show you how the model predictions change in a small ‘window’ of the feature around \(v\) for data instances in that window.”

Theory

How do PDP, M-plot, and ALE plot differ mathematically? Common to all three methods is that they reduce the complex prediction function \(\hat{f}\) to a function that depends on only one (or two) features. All three methods reduce the function by averaging the effects of the other features, but they differ in whether averages of predictions or of differences in predictions are calculated and whether averaging is done over the marginal or conditional distribution.

Partial dependence plots average predictions over the marginal distribution.

\[\begin{align*} \hat{f}_{S,PDP}(\mathbf{x}_S) &= \mathbb{E}_{X_C}[\hat{f}(\mathbf{x}_S,X_C)] \\ &= \int_{X_C}\hat{f}(\mathbf{x}_S,X_C)d\mathbb{P}(X_C) \end{align*}\]

This is the value of the prediction function \(f\), at feature value(s) \(\mathbf{x}_S\), averaged over all features in \(X_C\) (here treated as random variables). Averaging means calculating the marginal expectation \(\mathbb{E}\) over the features in set \(C\), which is the integral over the predictions weighted by the probability distribution. Sounds fancy, but to calculate the expected value over the marginal distribution, we simply take all our data instances, force them to have a certain grid value for the features in set \(S\), and average the predictions for this manipulated dataset. This procedure ensures that we average over the marginal distribution of the features.

M-plots average predictions over the conditional distribution.

\[\begin{align*} \hat{f}_{S,M}(\mathbf{x}_S) &= \mathbb{E}_{X_C|X_S}\left[\hat{f}(X_S,X_C)|X_S=\mathbf{x}_S\right] \\ &= \int_{X_C}\hat{f}(x_S, X_C)d\mathbb{P}(X_C|X_S = \mathbf{x}_S) \end{align*}\]

The only thing that changes compared to PDPs is that we average the predictions conditional on each grid value of the feature of interest, instead of assuming the marginal distribution at each grid value. In practice, this means that we have to define a neighborhood; for example, for the calculation of the effect of 30 m2 on the predicted house value, we could average the predictions of all houses between 28 and 32 m2.

ALE plots average the changes in the predictions and accumulate them over the grid (more on the calculation later).

\[\begin{align*} \hat{f}_{S,ALE}(\mathbf{x}_S) = & \int_{\mathbf{z}_{0,S}}^{\mathbf{x}_S} \mathbb{E}_{X_C|X_S = \mathbf{x}_S} \left[\hat{f}^S(X_S,X_C)|X_S = \mathbf{z}_S\right] d \mathbf{z}_S-\text{constant} \\ =& \int_{\mathbf{z}_{0,S}}^{\mathbf{x}_S}\left(\int_{\mathbf{x}_C}\hat{f}^S(\mathbf{z}_S,X_C)d\mathbb{P}(X_C|X_S = \mathbf{z}_S)\right) d \mathbf{z}_S-\text{constant} \end{align*}\]

The formula reveals three differences compared to M-plots. First, we average the changes of predictions, not the predictions themselves. The change is defined as the partial derivative (but later, for the actual computation, replaced by the differences in the predictions over an interval).

\[\hat{f}^S(\mathbf{x}_S,\mathbf{x}_C)=\frac{\partial\hat{f}(\mathbf{x}_S,\mathbf{x}_C)}{\partial \mathbf{x}_S}\]

The second difference is the additional integral over \(\mathbf{z}\). We accumulate the local partial derivatives over the range of features in set S, which gives us the effect of the feature on the prediction. For the actual computation, the z’s are replaced by a grid of intervals over which we compute the changes in the prediction. Instead of directly averaging the predictions, the ALE method calculates the prediction differences conditional on features S and integrates the derivative over features S to estimate the effect. Well, that sounds stupid. Derivation and integration usually cancel each other out, like first subtracting, then adding the same number. Why does it make sense here? The derivative (or interval difference) isolates the effect of the feature of interest and blocks the effect of correlated features.

The third difference of ALE plots to M-plots is that we subtract a constant from the results. This step centers the ALE plot so that the average effect over the data is zero.

One problem remains: Not all models come with a gradient; for example, random forests have no explicit gradient. But as you will see, the actual computation works without gradients and uses intervals. Let’s dive a little deeper into the estimation of ALE plots.

Estimation

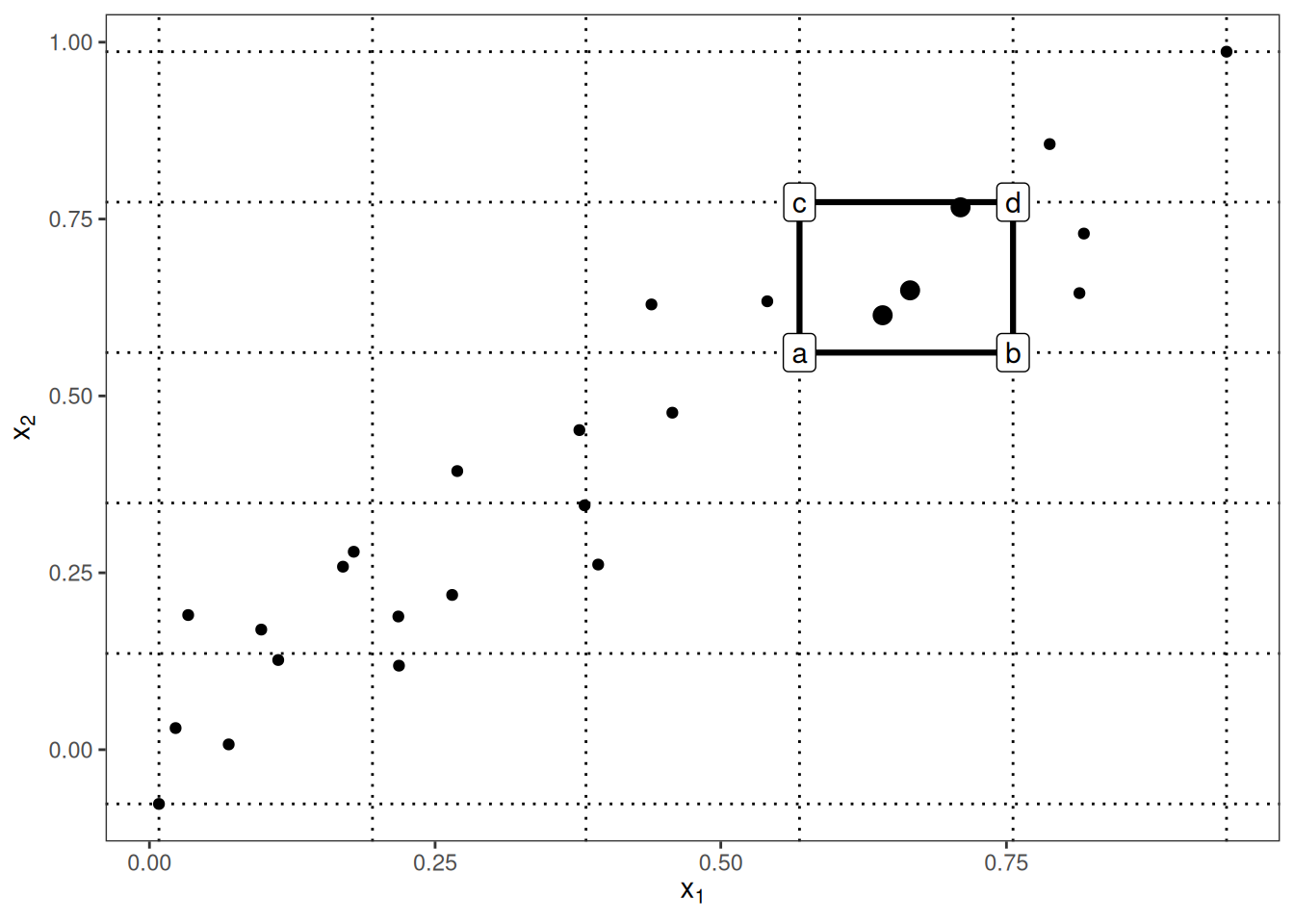

First I’ll describe how ALE plots are estimated for a single numerical feature, later for two numerical features, and for a single categorical feature. To estimate local effects, we divide the feature into many intervals and compute the differences in the predictions. This procedure approximates the derivatives and also works for models without derivatives.

First we estimate the uncentered effect:

\[\hat{\tilde{f}}_{j,ALE}(\mathbf{x}) = \sum_{k=1}^{k_j(\mathbf{x})} \frac{1}{n_j(k)} \sum_{i: x_j^{(i)} \in N_j(k)} \left[\hat{f}(z_{k,j}, \mathbf{x}^{(i)}_{-j}) - \hat{f}(z_{k-1,j}, \mathbf{x}^{(i)}_{-j})\right]\]

Let’s break this formula down, starting from the right side. The name Accumulated Local Effects nicely reflects all the individual components of this formula. At its core, the ALE method calculates the differences in predictions, whereby we replace the feature of interest with grid values \(z\). The difference in prediction is the Effect the feature has for an individual instance in a certain interval. The sum on the right adds up the effects of all instances within an interval, which appears in the formula as neighborhood \(N_j(k)\). We divide this sum by the number of instances in this interval to obtain the average difference of the predictions for this interval. This average in the interval is covered by the term Local in the name ALE. The left sum symbol means that we accumulate the average effects across all intervals. The (uncentered) ALE of a feature value that lies, for example, in the third interval is the sum of the effects of the first, second, and third intervals. The word Accumulated in ALE reflects this.

This effect is centered so that the mean effect is zero.

\[\hat{f}_{j,ALE}(\mathbf{x}) = \hat{\tilde{f}}_{j,ALE}(\mathbf{x}) - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \hat{\tilde{f}}_{j,ALE}(x_j^{(i)})\]

The value of the ALE can be interpreted as the main effect of the feature at a certain value compared to the average prediction of the data. For example, an ALE estimate of -2 at \(x^{(i)}_j = 3\) means that when the \(j\)-th feature has value 3, then the prediction is lower by 2 compared to the average prediction.

The quantiles of the distribution of the feature are used as the grid that defines the intervals. Using the quantiles ensures that there is the same number of data instances in each of the intervals. Quantiles have the disadvantage that the intervals can have very different lengths. This can lead to some weird ALE plots if the feature of interest is very skewed, for example, many low values and only a few very high values.

ALE plots for the interaction of two features

ALE plots can also show the interaction effect of two features. The calculation principles are the same as for a single feature, but we work with rectangular cells instead of intervals because we have to accumulate the effects in two dimensions. In addition to adjusting for the overall mean effect, we also adjust for the main effects of both features. This means that ALE for two features estimates the second-order effect, which does not include the main effects of the features. In other words, ALE for two features only shows the additional interaction effect of the two features. I spare you the formulas for 2D ALE plots because they are long and unpleasant to read. If you are interested in the calculation, I refer you to the paper by Apley and Zhu (2020), formulas (13) - (16). I’ll rely on visualizations to develop intuition about the second-order ALE calculation.

In the previous figure, many cells are empty due to the correlation. In the ALE plot, this can be visualized with a grayed-out or darkened box. Alternatively, you can replace the missing ALE estimate of an empty cell with the ALE estimate of the nearest non-empty cell.

Since the ALE estimates for two features only show the second-order effect of the features, the interpretation requires special attention. The second-order effect is the additional interaction effect of the features after we have accounted for the main effects of the features. Suppose two features do not interact, but each has a linear effect on the predicted outcome. In the 1D ALE plot for each feature, we would see a straight line as the estimated ALE curve. But when we plot the 2D ALE estimates, they should be close to zero because the second-order effect is only the additional effect of the interaction. ALE plots and PD plots differ in this regard: PDPs always show the total effect, while ALE plots show the first- or second-order effect. These are design decisions that do not depend on the underlying math. You can subtract the lower-order effects in a partial dependence plot to get the pure main or second-order effects, or you can get an estimate of the total ALE plots by refraining from subtracting the lower-order effects.

The accumulated local effects could also be calculated for arbitrarily higher orders (interactions of three or more features), but as argued in the PDP chapter, only up to two features makes sense because higher interactions cannot be visualized or even interpreted meaningfully.

ALE for categorical features

The accumulated local effects method needs – by definition – the feature values to have an order because the method accumulates effects in a certain direction. Categorical features do not have any natural order. To compute an ALE plot for a categorical feature, we have to somehow create or find an order. The order of the categories influences the calculation and interpretation of the accumulated local effects.

One solution is to order the categories according to their similarity based on the other features. The distance between two categories is the sum over the distances of each feature. The feature-wise distance compares either the cumulative distribution in both categories, also called the Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance (for numerical features), or the relative frequency tables (for categorical features). Once we have the distances between all categories, we use multi-dimensional scaling to reduce the distance matrix to a one-dimensional distance measure. This gives us a similarity-based order of the categories.

To make this a little bit clearer, here is one example: Let’s assume we have the two categorical features “season” and “weather” and a numerical feature “temperature”. For the first categorical feature (season), we want to calculate the ALEs. The feature has the categories “spring,” “summer,” “fall,” “winter.” We start to calculate the distance between categories “spring” and “summer.” The distance is the sum of distances over the features temperature and weather. For the temperature, we take all instances with season “spring,” calculate the empirical cumulative distribution function, and do the same for instances with season “summer” and measure their distance with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic. For the weather feature, we calculate for all “spring” instances the probabilities for each weather type, do the same for the “summer” instances, and sum up the absolute distances in the probability distribution. If “spring” and “summer” have very different temperatures and weather, the total category distance is large. We repeat the procedure with the other seasonal pairs and reduce the resulting distance matrix to a single dimension by multi-dimensional scaling.

If there is a meaningful order to the categories of a categorical feature, use this order for ALE.

ALE versus PDP

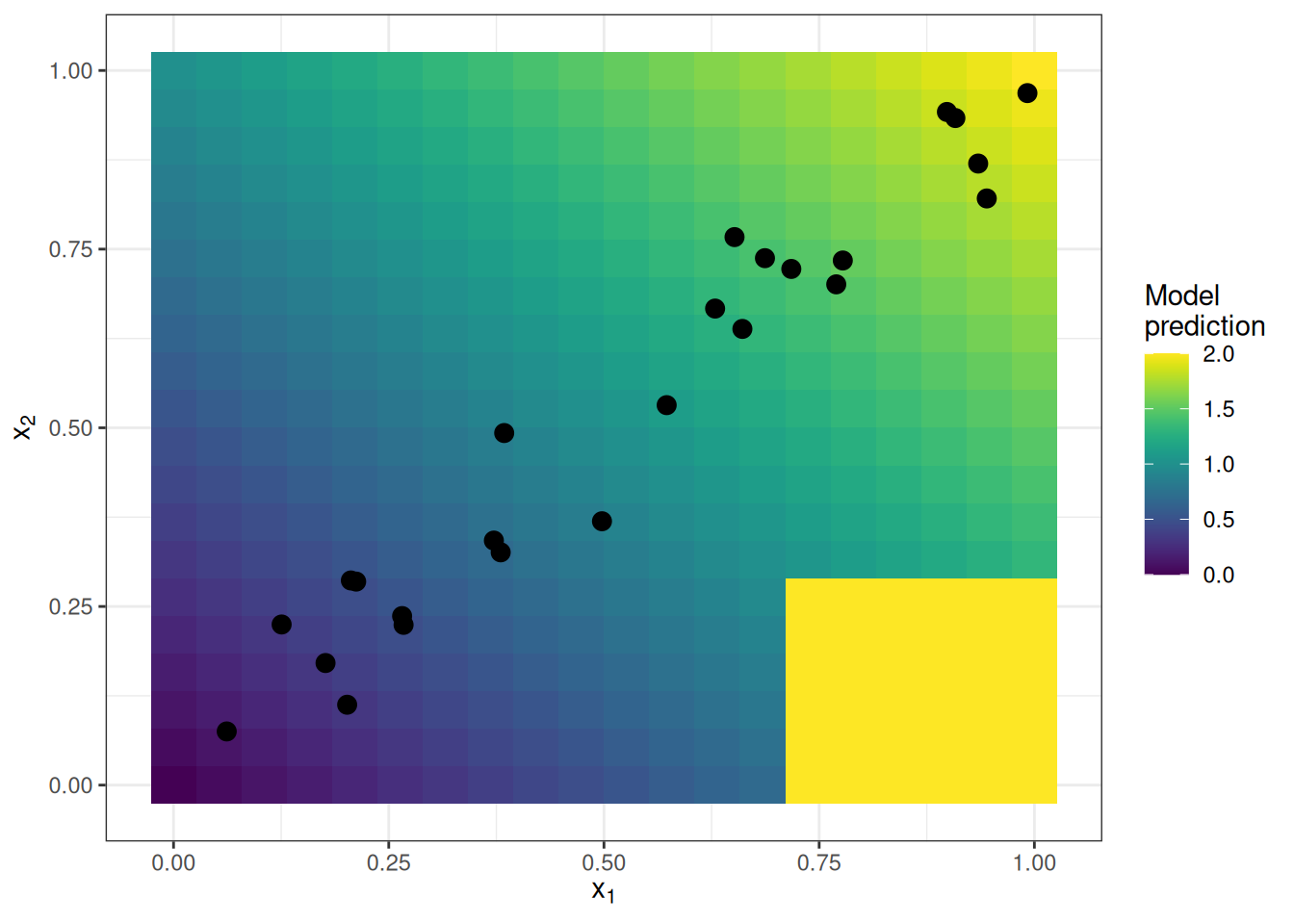

Let’s see ALE plots in action. I’ve constructed a scenario in which partial dependence plots fail. The scenario depicted in Figure 20.4 consists of a prediction model and two strongly correlated features. The prediction model is mostly a linear regression model but does something weird at a combination of the two features for which we have never observed instances. This “weird” area is far from the distribution of data (point cloud) and does not affect the performance of the model and, arguably, should not affect its interpretation.

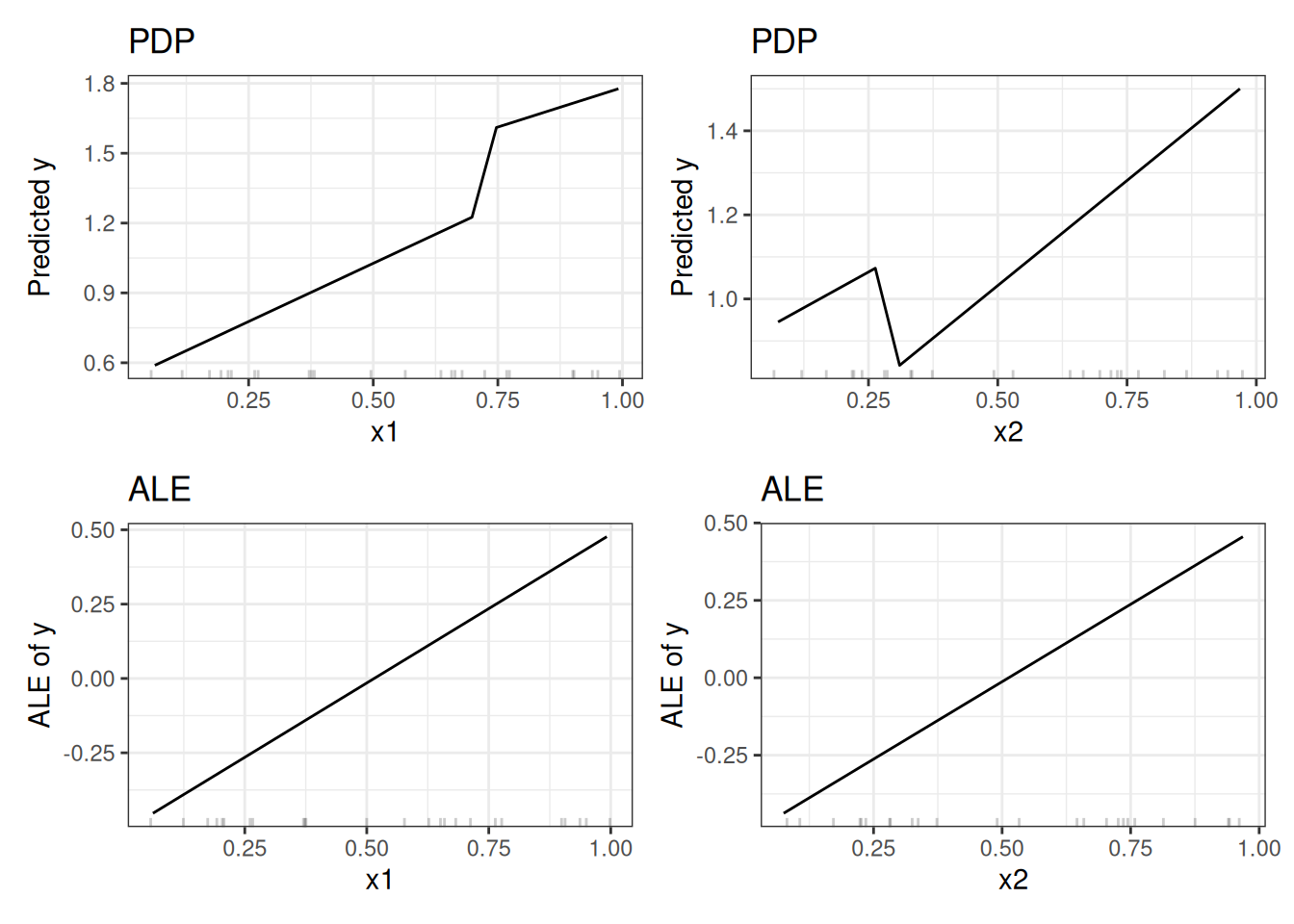

Is this a realistic, relevant scenario at all? When you train a model, the learning algorithm minimizes the loss for the existing training data instances. Weird stuff can happen outside the distribution of training data because the model is not penalized for doing weird stuff in these areas. Leaving the data distribution is called extrapolation, which can also be used to fool machine learning models, as described in the chapter on adversarial examples. See Figure 20.5 how the partial dependence plots behave compared to ALE plots. The PDP estimates are influenced by the odd behavior of the model outside the data distribution (steep jumps in the plots). The ALE plots correctly identify that the machine learning model has a linear relationship between features and predictions, ignoring areas without data.

But is it not interesting to see that our model behaves oddly at \(x_1 > 0.7\) and \(x_2 < 0.3\)? Well, yes and no. Since these are data instances that might be physically impossible or at least extremely unlikely, it is usually irrelevant to look into these instances. But if you suspect that your test distribution might be slightly different, and some instances are actually in that range, then it would be interesting to include this area in the calculation of feature effects. But it has to be a conscious decision to include areas where we have not observed data yet, and it should not be a side effect of the method of choice like PDP. If you suspect that the model will later be used with differently distributed data, I recommend using ALE plots and simulating the distribution of data you are expecting.

Anecdotal observation: For my applications, the ALE and PDP plots looked quite similar, despite correlation. Correlation can ruin the interpretability, but it doesn’t have to. If you ALE and PDP show the same curve for a correlated feature, just interpret the PDP since it has a simpler interpretation.

Examples

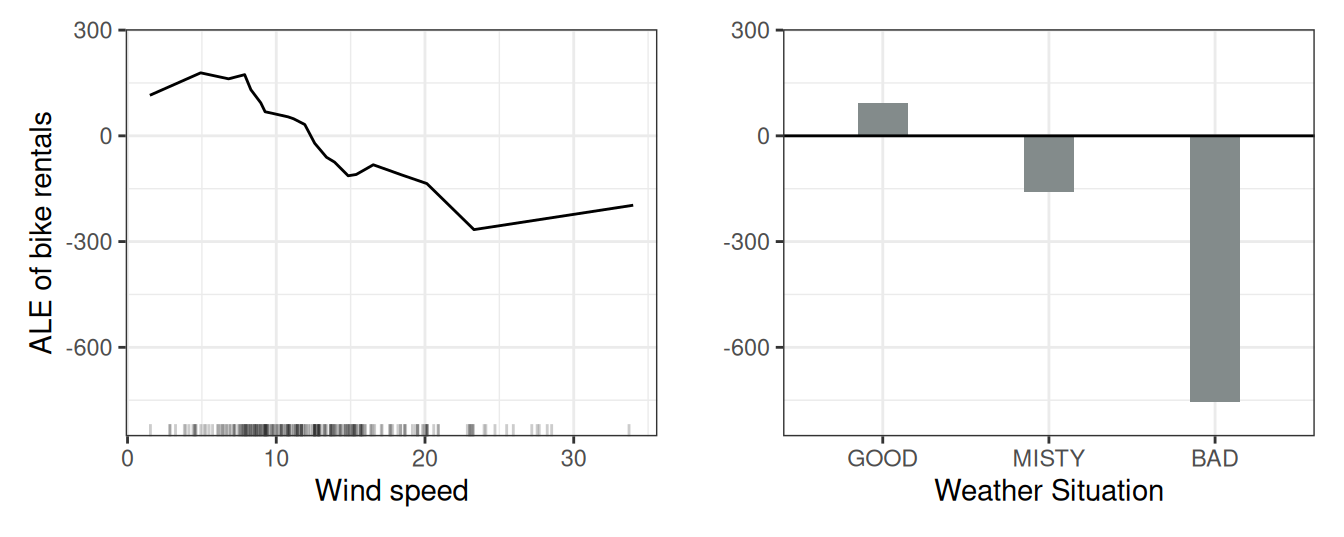

Turning to a real dataset, let’s predict the number of rented bikes based on weather and day, and check if the ALE plots really work as well as promised. We train a random forest to predict the number of rented bikes and use ALE plots to analyze how wind speed and weather influence the predictions.

Figure 20.6 (left) shows that an increasing wind speed has a negative effect on bike rentals. For the weather situation (right), we see that especially bad weather has a strong negative effect on the number of rented bikes. Both effects align with domain knowledge, which is a good sign.

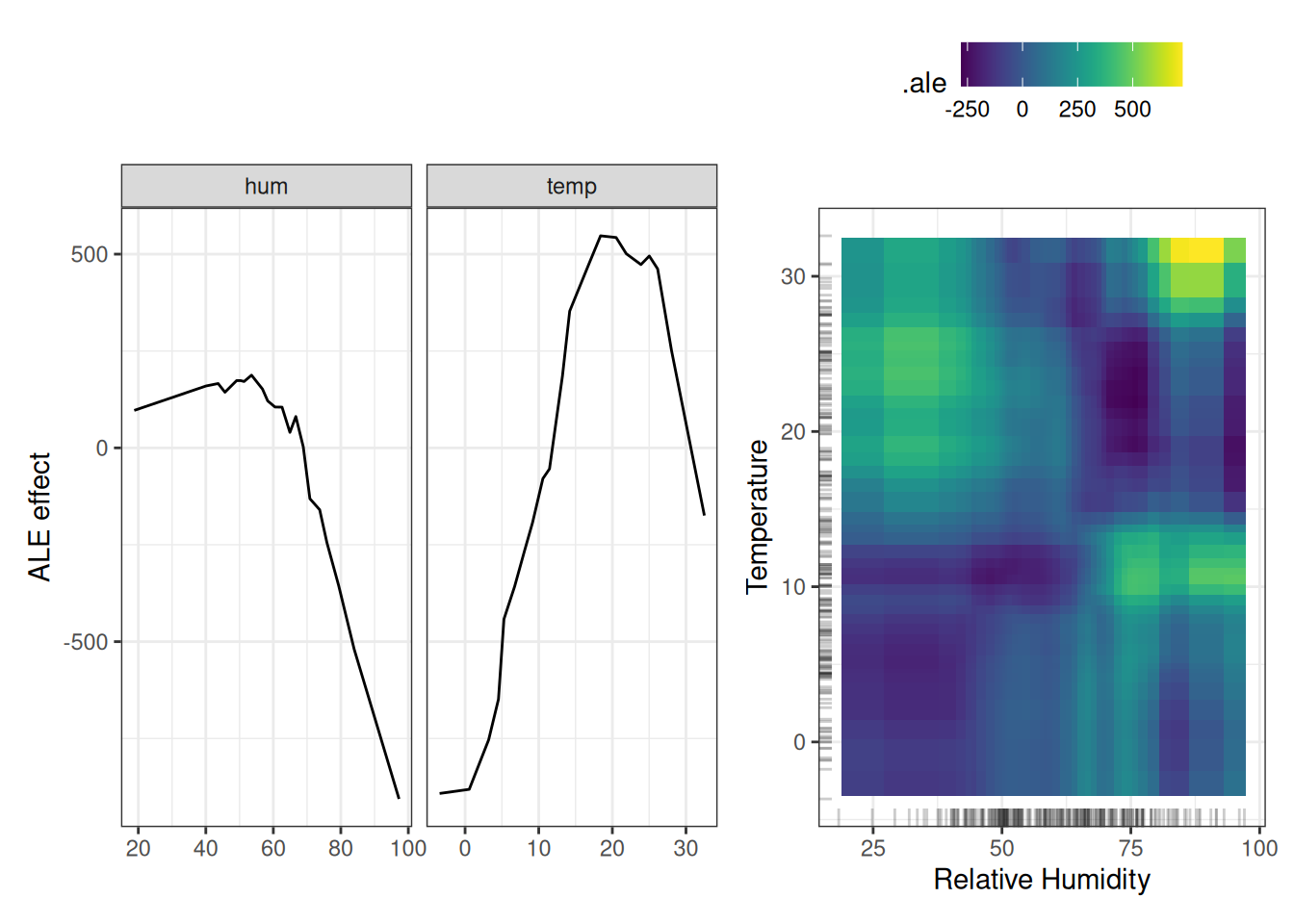

Next, we consider the effects of humidity and temperature, and their interaction on the predicted number of bikes. Remember that the second-order effect is the additional interaction effect of the two features and does not include the main effects. This means that, for example, you will not see the main effect that high humidity leads to a lower number of predicted bikes on average in the second-order ALE plot. Figure 20.7 shows both the main effects of temperature and humidity, and their interaction. The plot reveals an interaction: cold and humid weather increases the prediction. Keep in mind that both main effects of humidity and temperature say that the predicted number of bikes decreases in very cold and humid weather. In cold and humid weather, the combined effect of temperature and humidity is therefore not the sum of the main effects, but larger than the sum.

You can also get the total interaction effect by adding the two main effects and the mean prediction on top. If you are only interested in the interaction, you should look at the second-order effects because the total effect mixes the main effects into the plot. But if you want to know the combined effect of the features, you should look at the total effect. However, in a scenario where two features have no interaction, the total effect of the two features could be misleading because it probably shows a complex landscape, suggesting some interaction, but it is simply the product of the two main effects. The pure second-order effect would immediately show that there is no interaction.

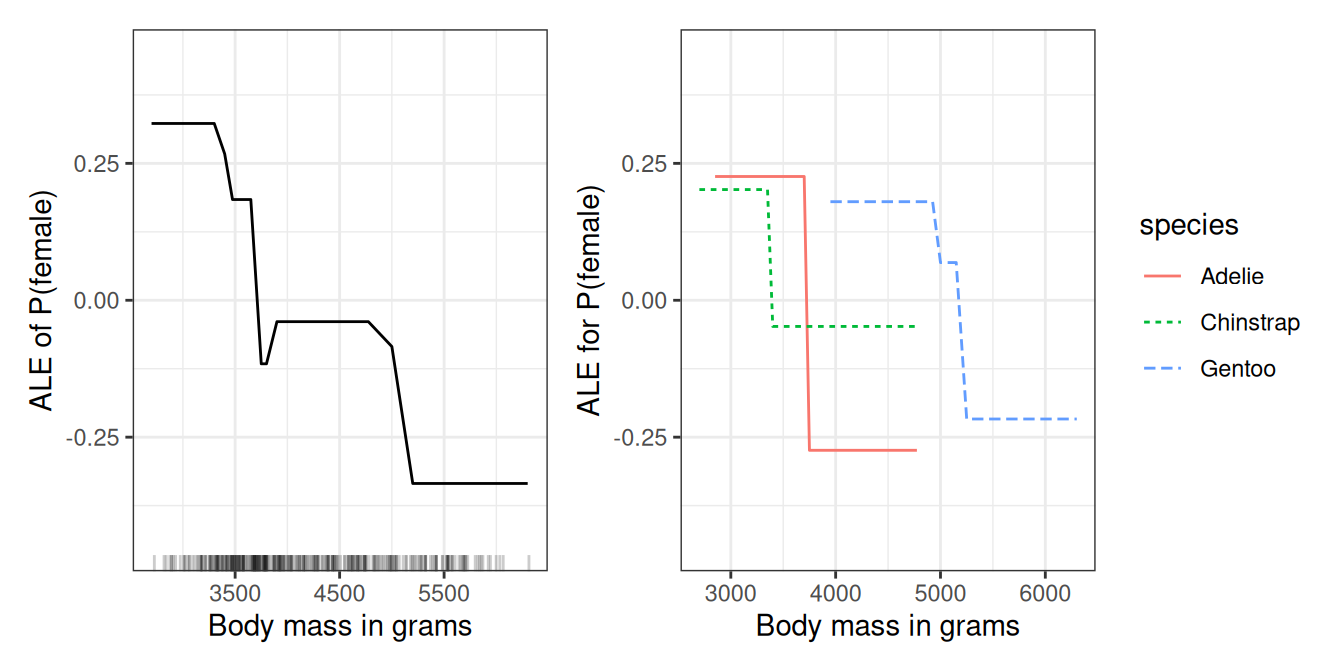

Enough bikes for now, let’s turn to a classification task. We train a random forest to predict the \(\mathbb{P}(Y = \text{female})\) based on body measurements. How does the body weight affect the probability of a penguin being female? Figure 20.8 (left) visualizes the ALE plot for body mass. The heavier the penguin, the less likely it is to be female. But we get a better picture when we visualize the ALE plots by species (Figure 20.8 on the right). Each of the species has a clear cut-off point, above which the body mass is more typical for male penguins. In general, the effects are quite similar to the PDPs in the PDP chapter.

Strengths

ALE plots are unbiased, which means they still work when features are correlated. Partial dependence plots fail in this scenario because they marginalize over unlikely or even physically impossible combinations of feature values.

ALE plots are faster to compute than PDPs and scale with O(n), since the largest possible number of intervals is the number of instances, with one interval per instance. The PDP requires n times the number of grid point estimations. For 20 grid points, PDPs require 20 times more predictions than the worst-case ALE plot, where as many intervals as instances are used.

The (local) interpretation of ALE plots is clear: Conditional on a given value, the relative effect of changing the feature on the prediction can be read from the ALE plot. ALE plots are centered at zero. This makes their interpretation nice because the value at each point of the ALE curve is the difference to the mean prediction. The 2D ALE plot only shows the interaction: If two features do not interact, the plot shows nothing.

The entire prediction function can be decomposed into a sum of lower-dimensional ALE functions, as explained in the chapter on functional decomposition.

All in all, in most situations I would prefer ALE plots over PDPs because features are usually correlated to some extent.

Limitations

An interpretation of the effect across intervals is not permissible if the features are strongly correlated. Consider the case where your features are highly correlated, and you are looking at the left end of a 1D-ALE plot. The ALE curve might invite the following misinterpretation: “The ALE curve shows how the prediction changes, on average, when we gradually change the value of the respective feature for a data instance, and keeping the instances’ other feature values fixed.” The effects are computed per interval (locally) and therefore the interpretation of the effect can only be local. For convenience, the interval-wise effects are accumulated to show a smooth curve, but keep in mind that each interval is created with different data instances.

ALE effects may differ from the coefficients specified in a linear regression model when features interact and are correlated. Grömping (2020) showed that in a linear model with two correlated features and an additional interaction term (\(\hat{f}(x) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \beta_3 x_1 x_2\)), the first-order ALE plots do not show a straight line. Instead, they are slightly curved because they incorporate parts of the multiplicative interaction of the features. To understand what is happening here, I recommend reading the chapter on functional decomposition. In short, ALE defines first-order (or 1D) effects differently than the linear formula describes them. This is not necessarily wrong, because when features are correlated, the attribution of interactions is not as clear. But it is certainly unintuitive that ALE and linear coefficients do not match.

ALE plots can become a bit shaky (many small ups and downs) with a high number of intervals. In this case, reducing the number of intervals makes the estimates more stable, but also smooths out and hides some of the true complexity of the prediction model. There’s no perfect solution for setting the number of intervals. If the number is too small, the ALE plots might not be very accurate. If the number is too high, the curve can become shaky. To compromise smoothness and accuracy, Gkolemis et al. (2023) proposed an automated bin-splitting approach that progressively enlarges bins (for more stable estimates) as long as the local effects within them remain relatively constant (for preserving the model’s true complexity).

Unlike PDPs, ALE plots are not accompanied by ICE curves. For PDPs, ICE curves are great because they can reveal heterogeneity in the feature effect, which means that the effect of a feature looks different for subsets of the data. For ALE plots, you can only check per interval whether the effect is different between the instances, but each interval has different instances, so it is not the same as ICE curves.

Second-order ALE estimates have a varying stability across the feature space, which is not visualized in any way. The reason for this is that each estimation of a local effect in a cell uses a different number of data instances. As a result, all estimates have a different accuracy (but they are still the best possible estimates). The problem exists in a less severe version for main effect ALE plots. The number of instances is the same in all intervals, thanks to the use of quantiles as a grid, but in some areas, there will be many short intervals, and the ALE curve will consist of many more estimates. But for long intervals, which can make up a big part of the entire curve, there are comparatively fewer instances.

Second-order effect plots can be a bit annoying to interpret, as you always have to keep the main effects in mind. It’s tempting to read the heat maps as the total effect of the two features, but it is only the additional effect of the interaction. The pure second-order effect is interesting for discovering and exploring interactions, but for interpreting what the effect looks like, I think it makes more sense to integrate the main effects into the plot.

The implementation of ALE plots is much more complex and less intuitive compared to partial dependence plots.

Even though ALE plots are not biased in the case of correlated features, interpretation remains difficult when features are strongly correlated. Because if they have a very strong correlation, it only makes sense to analyze the effect of changing both features together and not in isolation. This disadvantage is not specific to ALE plots, but a general problem of strongly correlated features.

If the features are uncorrelated and computation time is not a problem, PDPs are slightly preferable because they are easier to understand and can be plotted along with ICE curves.

The list of disadvantages has become quite long, but do not be fooled by the number of words I use. As a rule of thumb: Use PDP if features are not correlated. If feature are correlated, but PDP and ALE show more or less the same curves, go for the simpler PDP interpretation. If feature are correlated and PDP and ALE differ, go with the ALE plot.

Software and alternatives

Did I mention that partial dependence plots and individual conditional expectation curves are an alternative? =)

ALE plots are implemented in R in the ALEPlot R package by the inventor himself, and once in the iml package. ALE also has a couple of Python implementations: effector, ALEPython, Alibi, and PiML.